Back to Top

Mark Jacobs' Mathematical Excursions

Mathematical Theorems about Men and Women

- A man will pay $2 for a $1 item he needs.

- A woman will pay $1 for a $2 item that she doesn't need.

- A woman worries about the future until she gets a husband.

- A man never worries about the future until he gets a wife.

- A successful man is one who makes more money than his wife can spend.

- A successful woman is one who can find such a man.

- To be happy with a man, you must understand him a lot and love him a little.

- To be happy with a woman, you must love her a lot and not try to understand her at all.

- Married men live longer than single men, but married men are a lot more willing to die.

- Any married man should forget his mistakes, there's no use in two people remembering the

same thing.

- Men wake up as good-looking as they went to bed. Women somehow deteriorate during the

night.

- A woman marries a man expecting he will change, but he doesn't.

- A man marries a woman expecting that she won't change, and she does.

- A woman has the last word in any argument.

- Anything a man says after that is the beginning of a new argument.

Transcendental Algebraic Equations

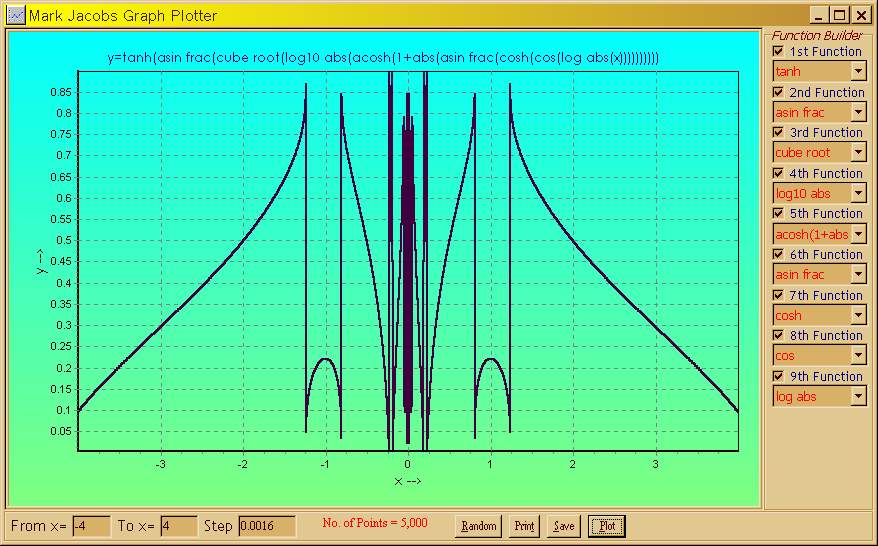

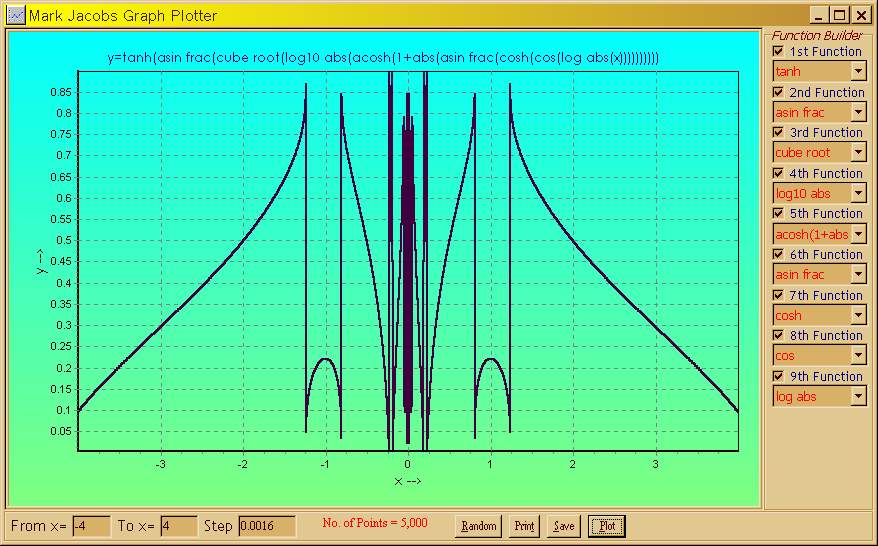

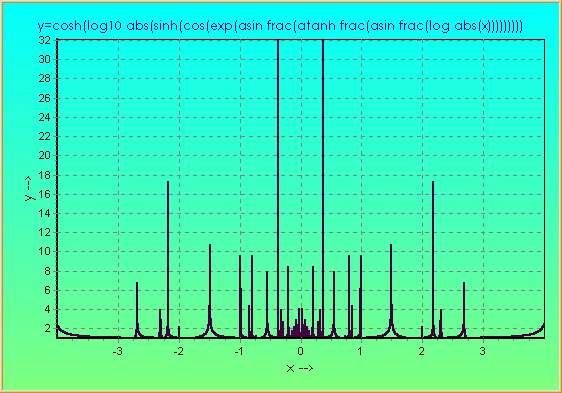

A long-time obsession of mine has been transcendental algebraic equations, which despite

sounding a long way away from the real world, threw up a real gem of a function the other

night. I have a function plotter that will map out phenomenally complex equations of

the single variant variety. It looks like this (click on image to download the zip file) :-

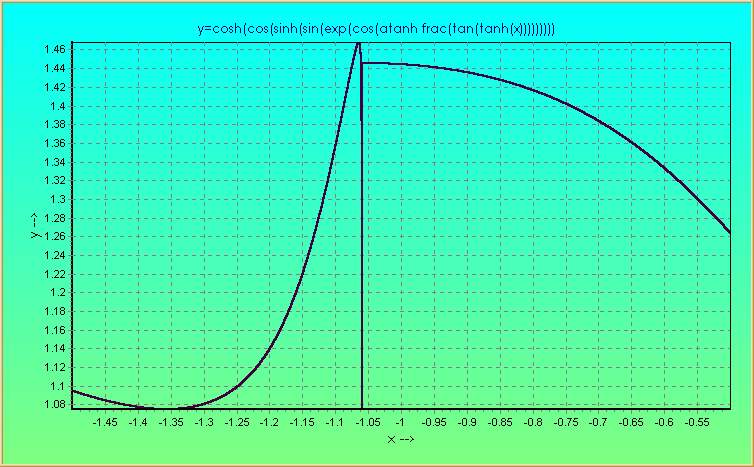

Trying out a few randomisations, I began to recognise patterns and groups of curves and

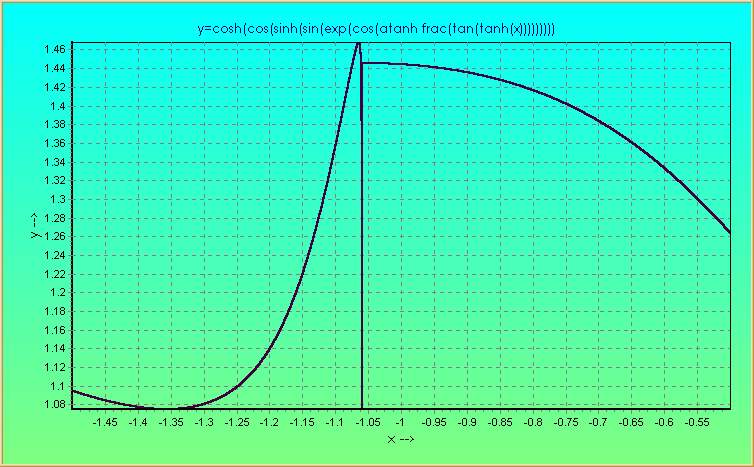

asymptotes. Then a level 9 function produced this :-

The amazing thing about this curve is that it seems to go along smoothly,

then flips out completely, but finitely, and then continues along smoothly in the same

direction and from the same area as where the flip-out started. I call this the first

portrayal of a mathematically rigorous representation of a quantum jump. For example,

consider an electron orbiting a nucleus. Prior to the point of flip-out

(or supposed asymptote), the electron is in a steadily-changing energy field which is

drawing the electron out of its current orbit, then a sudden plummeting followed by

an even more sudden rise, as the electron joins its new orbit, which continues on smoothly.

Many other representations may be inferred from this graph, but it's just one of many

that can be generated. This is my "pet" application and it was ported from a programmable

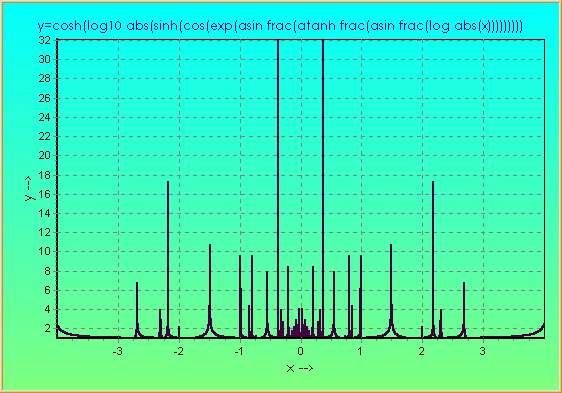

Casio calculator. Here is another one portraying Electron Shell Mappings :-

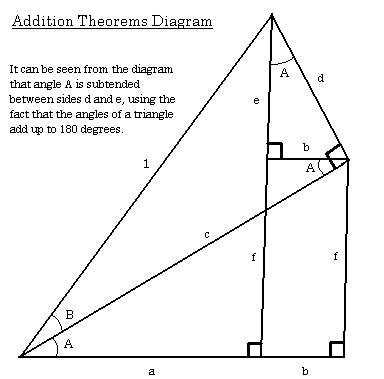

Trigonometrical Addition Theorems and Repercussions

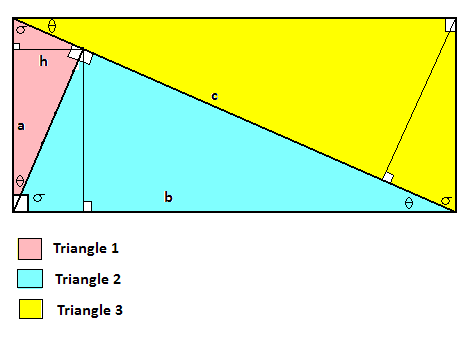

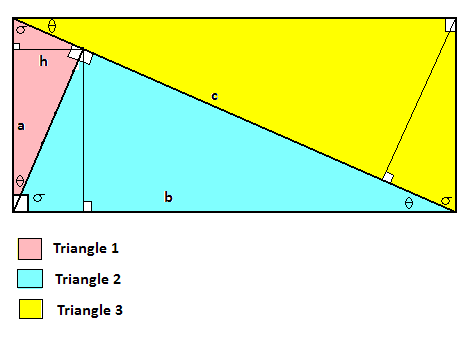

First, let's do a simple proof of Pythagoras' theorem :-

It can be seen from the diagram that the areas of triangles 1 and 2 add up to the area of

triangle 3. It can be also seen that the angles in all 3 triangles are equal to each other

(look at the angles θ and σ in the diagram) and therefore, the triangles are

mathematically similar to each other. This means that each triangle can be scaled to exactly

fit either of the other 2 triangles by multiplying each of the sides by a fixed factor. This

also applies to the triangles' heights. Let's call the height of triangle 1's right-angle above

its base, h. Then, using scaling, triangle 2's height would be :-

hb/a

and triangle 3's height would be :-

hc/a

In terms of areas of triangles (half base times height), we would have :-

1) Triangle 1 Area = ½ah

2) Triangle 2 Area = ½bhb/a

3) Triangle 3 Area = ½chc/a

But we already know that (1)+(2)=(3) (triangle areas 1 and 2 add up to 3), so adding equations and doubling, we get :-

ah + b²h/a = c²h/a

Dividing by h throughout and multiplying both sides by a, we get :-

a² + b² = c²

Once you have accepted that

a² + b² = c²

in the case of a right-angled triangle where c is the hypotenuse, it becomes quite

interesting how things turn out for the relationships between the angles and sides

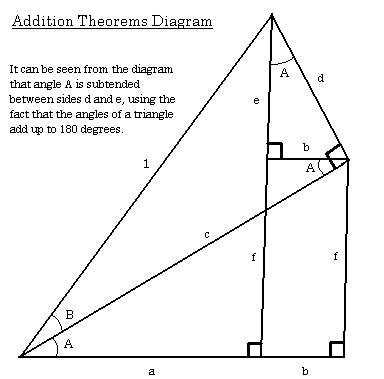

of a triangle. The following diagram is representative of a couple of simple, but

sweet theorems, which lead nicely on to the next section on sine and cosine laws.

Using Pythagoras we see that

c² + d² = 1

Using definitions of sine and cosine we get

1) c = cos B

2) d = sin B

Hence

sin² B + cos² B = 1

Continuing, we get

3) a + b = c cos A = cos B cos A from (1) and

4) b = d sin A = sin B sin A from (2).

We also know

cos (A + B) = a = (a + b) - b

Hence from (3) and (4), we get

cos (A + B) = cos A cos B - sin A sin B

Similarly,

sin (A + B) = e + f = d cos A + c sin A = sin A cos B + sin B cos A

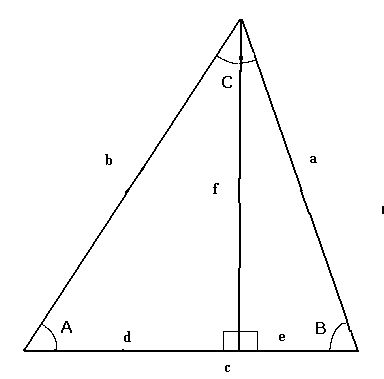

Sine and Cosine Laws for any Triangle

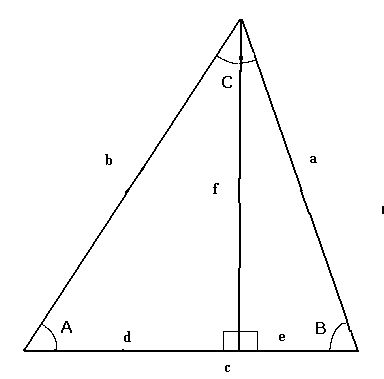

The next diagram shows how to derive the sine and cosine laws for triangles.

1) A + B = 180° - C

2) cos (180° - C) = - cos C

3) f = b sin A

4) f = a sin B

5) d = b cos A

6) e = a cos B

(3) and (4) yield the sine law in

7) a / sin A = b / sin B

Again, using Pythagoras, we can see from the diagram that

8) d² + f² = b²

9) e² + f² = a²

Adding (8) and (9), we get

a² + b² = d² + e² + 2 f²

a² + b² = (d + e)² - 2 d e + 2 f²

Using (4), (5), and (6), we get

a² + b² = c² - 2 a b cos A cos B + 2 a² sin² B

Using a rearranged (7), so that a sin B = b sin A, we get

a² + b² = c² - 2 a b (cos A cos B - sin A sin B)

Now, we use the Addition Theorem above for cosine to simply the bracket contents and rearrange to get

c² = a² + b² + 2 a b cos (A + B)

Putting (1) and (2) together, we get cos (A + B) = - cos C, giving the final equation :-

c² = a² + b² - 2 a b cos C

This looks like a crooked variety of Pythagoras, bent by the fact that there may not be

a right angle. When C is 90°, cos 90° is zero, so it is Pythagoras.

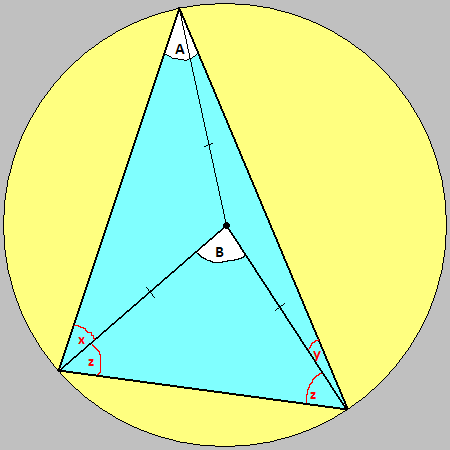

Circle Geometry and Angles Subtended by Chords

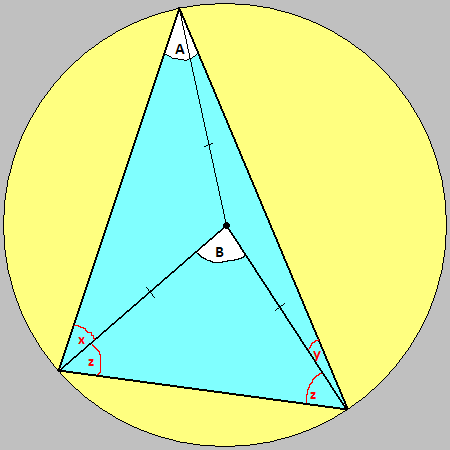

The angle A in the above and below diagrams, is exactly twice the size of angle B, wherever you draw the

chord or the point on the circumference (as long as it's above the chord). B is the angle

subtended by the chord at the centre of the circle, and A is the angle subtended at the

circumference. Lines with a fleck through them are equal in length and are radii of the circle.

To prove this, we use a property of isosceles triangles : the angles opposite

the equal sides are also equal. And that the angles of a triangle add up to 180°.

1) A = x + y

x + x + y + y + z + z = 180°

Therefore, x + y + z = 90°

Rearranging, 2) z = 90° - x - y

Now, B = 180° - z - z

So from (2), B = 180° - 90° + x + y - 90° + x + y

Simplifying, B = 2(x + y)

Using (1), we get B = 2A

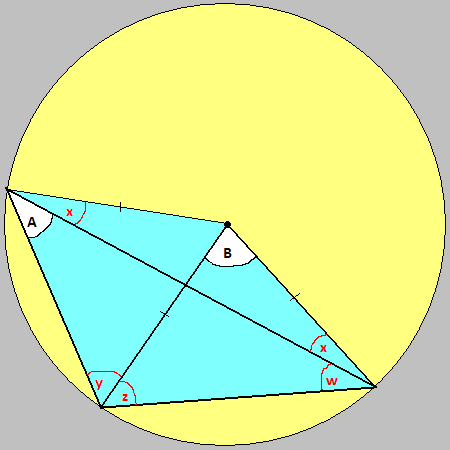

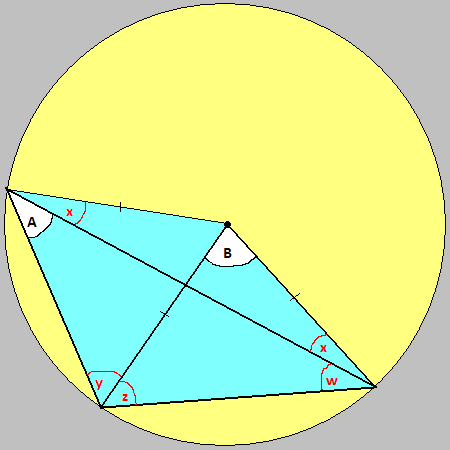

In this case, angle A has been subtended at a point swung round the circumference to the left.

Despite this, we can still prove the same, no matter how small angle w becomes.

A + x = y

Hence, 3) y - x = A

Also, B + 2z = 180°

4) 2z = 180° - B

Now, 5) A + y + z + w = 180°

But, z = x + w

6) w = z - x

So, using (6) in (5), we get A + y + z + z - x = 180°

7) A + y - x + 2z = 180°

Using (4) in (7), we get A + y - x + 180° - B = 180°

A + y - x = B

Using (3), we obtain B = 2A

This is true even as the angle w tends to zero, which is surprising because one would expect

angle A to tend to 0 rather than remain fixed. The reason is because the point on the

circumference gets ever closer to the end of the subtending chord, and so the line rendering

the angle gets ever shorter, hence w can become really small, but angle A remains the same.

The Golden Ratio and Why it's Important

Almost like a measure of beauty, the golden ratio has been speculated about by mathematicians

from time immemorial. It appears throughout nature, and we instinctively find things with its

dimensions beautiful.

ϕ (the golden ratio - phi) is defined as the ratio of the length

of the longest side of a rectangle to the shortest, where, if the largest possible square

portion is removed from the rectangle, you'd be left with a smaller rectangle with exactly the

same ratio of longest to shortest sides. This inviolability of the rectangle's aspect ratio

gives rise to fractal iterative effects, as if trying to zoom in infinitely.

Here are some links about its presence in nature :-

https://io9.gizmodo.com/15-uncanny-examples-of-the-golden-ratio-in-nature-5985588

https://science.howstuffworks.com/math-concepts/fibonacci-nature1.htm

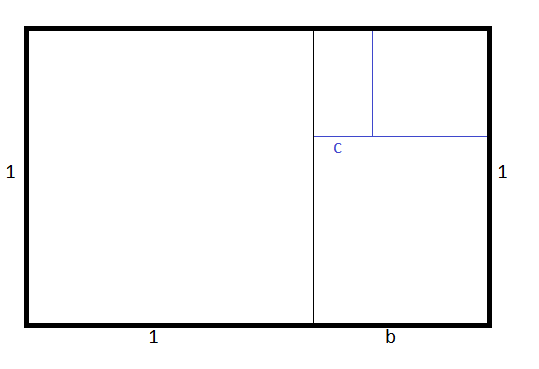

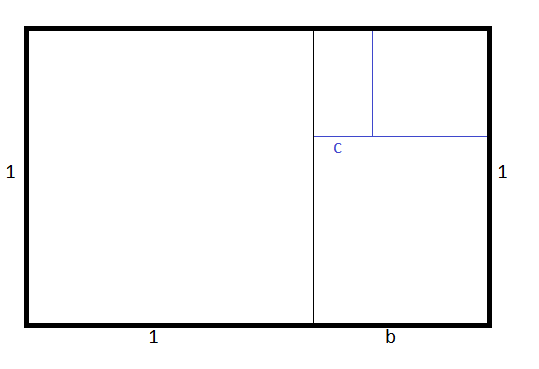

The mathematical definition of the golden ratio is based on the ratio of one side to the other in a rectangle as follows.

In the above diagram, the golden ratio is the ratio of b+1 to 1.

1) ϕ = (b + 1) / 1 = b + 1

Because ratio (b+1) to 1 is the same as the ratio 1 to b (removing the 1 by 1 square, leaves a rectangle 1 by b in dimensions) :-

2) b + 1 = 1 / b where b < 1.

b² + b = 1

3) b² + b - 1 = 0

This is a quadratic equation of the form ax² + bx + c = 0, and the formula for its solution is

4) x = ( -b ± √( b² - 4ac) ) / 2a

Plugging in the coefficients from (3) of 1, 1 and -1 for a, b, c in (4), we get

b = ( -1 ± √( 1² + 4) ) / 2

b = ( -1 ± √5 ) / 2

Because b<1 in (2), and b cannot be negative, the solution we require is

b = ( √5 - 1 ) / 2

and the golden ratio is b+1 (1), so

ϕ = ( √5 - 1 +2 ) / 2 = ( √5 + 1 ) / 2 ≈ 1.61803398874989

This ratio crops up in all sorts of places. Look at the ratio of consecutive terms in a Fibonacci sequence, and you'll see they tend to the golden ratio.

Fibonacci sequence 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, ...

Ratios (3 dps.) 1, 2, 1.5, 1.667, 1.6, 1.625, 1.615, 1.619, 1.618, ...

and is fairly rapidly convergent. This is therefore an attractive number, because even series want to get to it quickly!

Miscellaneous Distractions

45/52-e/pi = 0.00012863595235031

2996863034895 · 2^1290000 ± 1 gives twin primes!